The U.S. Supreme Court is poised to issue a decision this month in a case that could again threaten a key aspect of President Barack Obama’s health law.

But this time around, unlike three years ago when the court rejected a constitutional challenge to the law’s individual mandate, the case, King v. Burwell, focuses primarily on statutory interpretation.

The issue is whether section 36B means what it seems to say if read literally and in isolation from the rest of the law: that Affordable Care Act subsidies are available only to people “enrolled … through an exchange established by the state.”

And the different interpretations have proven dicey — so much so that each side in the case is having trouble explaining away the evidence supporting the contrary position.

Solicitor General Donald Verrilli and other defenders of the subsidies have failed to suggest any very plausible reason — other than sloppy draftsmanship, on which Verrilli has not much relied — why Congress said “established by the state” if it intended that subsidies also be available in the federally established exchange.

On the other hand, ACA opponents who read “established by the state” literally have produced little evidence that the law’s drafters deliberately and quietly planted in an obscure subclause the words that could become the seeds of the law’s destruction.

Plaintiffs in the case suggest that the drafters inserted these four words in order to pressure states to establish their own exchanges. But the legislative history offers scant evidence of this intent. And the three dozen states in question either failed to notice or disregarded it.

How these explanations sway the justices — or at least five of them — will determine whether the language drafted by Congress means that nearly 6.4 million low-and-middle-income people are not eligible for the overhaul’s tax subsidies because they live in a state that chose to rely on the federal government’s healthcare.gov, rather than establish its own online insurance marketplace. The subsidies make insurance affordable to many of the people who seek Obamacare coverage because they don’t get health coverage through their employers.

If the court rules that the subsidies are available only in states — mostly blue — that established their own exchanges, insurance markets in the other three dozen or so states might collapse. Unless Congress or the states reliant on healthcare.gov were to move fast to limit the damage, few people in those states would buy individual insurance. Those who did would likely have health problems and premiums would soar.

Many ACA opponents say that section 36B “means what it says,” as conservative Justice Antonin Scalia implied at the March 4 oral argument, even if the wording “may not be the statute [Congress] intended” and even assuming that it might “produce disastrous consequences.”

To the contrary, say Verrilli and other supporters, the law’s overall text, structure, design and history make clear that Congress intended to make subsidies available in all 50 states. They say the challengers’ interpretation would defeat the law’s purpose of making health insurance widely affordable. The Internal Revenue Service came to the same conclusion in an interpretive rule, to which Verrilli argued the justices should defer if in doubt.

As in 2012, the stakes in King v. Burwell are so high that Obama has made it clear that he would attack any decision that would cripple the health law as legally indefensible and politically motivated.

“[T]his should be an easy case,” Obama said June 8. “Frankly, it probably shouldn’t even have been taken up … based on a twisted interpretation of four words. … I’m optimistic that the Supreme Court will play it straight.” The next day, he added (without specific reference to the court) that “it seems so cynical to want to take health care away from millions of people.”

These shots across the court’s bow came even though Scalia and Justice Samuel Alito had strongly suggested during the argument that they would vote against the administration’s position.

Alito also suggested the possibility of delaying until 2016 the effective date of any decision against the administration. Such a delay, he said, would give the states and Congress time to avoid the disruption that would be caused if the court ruled the premium subsidies now available in the three-dozen states using healthcare.gov are illegal.

Justice Clarence Thomas, who was silent as usual during the arguments, is expected to vote with Scalia and Alito. The four liberal justices — Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan — seemed poised to line up with Obama. So the president will win if either Chief Justice John Roberts or Justice Anthony Kennedy sides with him.

While Kennedy’s vote is still up in the air, ACA supporters were cheered by his assertion to the lawyer challenging the subsidies that “there’s a serious constitutional problem if we adopt your argument.” Kennedy reasoned that the states are being unconstitutionally “coerced” if, as the challengers argue, the law requires them either to establish their own exchanges or see their residents disqualified from the subsidies.

The only way to avoid constitutional problems, suggested Kennedy, may be to resolve any ambiguities in Obama’s favor. This seemed inconsistent with the suggestions by Scalia, Alito and the challengers that the relevant language is free of ambiguity and without constitutional problems.

Roberts was sphinxlike during the argument in King v. Burwell. The case puts him in an unenviable position.

When Roberts stunned court-watchers by joining the four liberal justices and upholding the individual mandate in the 2012 decision, National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, he was bitterly assailed by his usual allies — Kennedy, Scalia, Thomas and Alito — and was called a traitor by many other conservatives.

This barrage was intensified by a well-sourced news report that Roberts had initially voted to strike down the individual mandate and changed his mind — provoking a huge battle inside the court — after liberals led by Obama had preemptively denounced any decision to strike down the law as politically motivated, conservative “judicial activism.”

The conservative denunciations of Roberts will be even more bitter if he sides with Obama this time, too. On the other hand, if Roberts votes with the other four Republican appointees to gut the Democratic president’s signature accomplishment, it will feed the kind of attacks that the chief justice dreads on the Roberts court’s conservative majority as a bunch of robed politicians.

Looking to the future, a ruling against Obama could be extremely awkward politically for Republican members of Congress, presidential candidates and officials in the mostly red, affected states, even though it might be cheered (at least initially) by Republican voters.

In this scenario, the president and other Democrats would immediately demand that Republicans help them save the subsidies of millions of people at risk of losing their health insurance, by adopting new legislation.

Some Republicans say this would be an opportunity to extract compromises from Obama such as more choices for consumers – especially less expensive, less comprehensive health insurance options; the elimination of the mandate to buy insurance; or restrictions on medical malpractice lawsuits.

Others predict a humiliating and internally divisive Republican cave-in to avoid being blamed for the “disastrous consequences” that Justice Scalia hypothesized.

Whatever the outcome, the chief justice, in his tenth year on the Court, is in for a long, hot summer.

Stuart Taylor Jr. is a Washington writer, lawyer and Brookings nonresident senior fellow.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

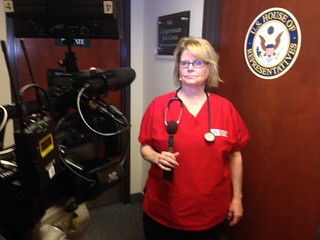

“I came out today because it’s important to get Costa to reverse his ‘yes’ vote on aspects of a trade agreement which would cause the public to pay more for medications and let corporations overturn laws, like nurse-to-patient ratios, if they were seen as barriers to profit,” says Susan Burr, RN, of Kaiser Fresno. Burr, along with other National Nurses United members and community organizations, joined a sit-in at Rep. Costa’s office Tuesday morning to hold Costa accountable.

“I came out today because it’s important to get Costa to reverse his ‘yes’ vote on aspects of a trade agreement which would cause the public to pay more for medications and let corporations overturn laws, like nurse-to-patient ratios, if they were seen as barriers to profit,” says Susan Burr, RN, of Kaiser Fresno. Burr, along with other National Nurses United members and community organizations, joined a sit-in at Rep. Costa’s office Tuesday morning to hold Costa accountable. At today’s sit-in, RNs and community groups turned up the heat on Rep. Costa to reverse his position. According to nurses, his staff responded in kind, literally—by shutting off the air conditioning. While trying to sweat out the nurses and community groups, Costa’s staff also refused the bathroom key and eventually called an officer from the Department of Homeland Security (who allowed the sit in to continue). The RNs stayed throughout the morning, speaking to media and also monitoring members of local community groups who were on a hunger strike.

At today’s sit-in, RNs and community groups turned up the heat on Rep. Costa to reverse his position. According to nurses, his staff responded in kind, literally—by shutting off the air conditioning. While trying to sweat out the nurses and community groups, Costa’s staff also refused the bathroom key and eventually called an officer from the Department of Homeland Security (who allowed the sit in to continue). The RNs stayed throughout the morning, speaking to media and also monitoring members of local community groups who were on a hunger strike.