AHRQ Grant Awards

Category Archives: Nursing News

Plan to Attend 2015 ANA Ethics Symposium

ANA President Addresses Ethics in The Washington Post

Medicaid Expansion Helps Cut Rate Of Older, Uninsured Adults From 12 To 8 Percent

The health law’s expansion of Medicaid coverage to adults with incomes over the poverty line was key to reducing the uninsured rate among 50- to 64-year-olds from nearly 12 to 8 percent in 2014, according to a new analysis.

“Clearly most of the gains in coverage were in Medicaid or non-group coverage,” says study co-author Jane Sung, a senior strategic policy adviser at the AARP Public Policy Institute, which conducted the study with the Urban Institute.

Under the health law, adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level ($16,243 for one person in 2015) are eligible for Medicaid if a state decides to expand coverage. Twenty-seven states had done so by the end of 2014.

The study found the uninsured rate for people between age 50 and 64 who live in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid was twice as high—11 percent—as for those who live in states that have done so.

More than 2 million people between 50 and 64 gained coverage between December 2013 and December 2014, according to the study.

The figures are based on the Urban Institute’s quarterly Internet-based Health Reform Monitoring Survey, which includes 8,000 adults between age 50 and 64.

During the same time period, the uninsured rate among all adults between age 18 and 64 fell from 17.5 percent to 12.8 percent, says Laura Skopec, a research associate at the Urban Institute who co-authored the study. Other studies that have looked at the population overall also have shown deeper cuts in the uninsured rate in states that expanded Medicaid.

Many people in the older 50 to 64 age group have employer-sponsored insurance, Skopec says. But until the health law passed, “those who didn’t have access to employer-sponsored coverage didn’t have very good options.”

In addition to expanding Medicaid coverage, the health law prohibits insurers from charging older people premiums that are more than three times higher than those for younger people. The law’s prohibition against insurers refusing to cover people because they have pre-existing medical conditions has also helped many older people gain coverage, Skopec says.

Please contact Kaiser Health News to send comments or ideas for future topics for the Insuring Your Health column.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

The Gray Areas Of Assisted Suicide

SAN FRANCISCO — Physician-assisted suicide is illegal in all but five states. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen in the rest. Sick patients sometimes ask for help in hastening their deaths, and some doctors will hint, vaguely, how to do it.

This leads to bizarre, veiled conversations between medical professionals and overwhelmed families. Doctors and nurses want to help but also want to avoid prosecution, so they speak carefully, parsing their words. Family members, in the midst of one of the most confusing and emotional times of their lives, are left to interpret euphemisms.

That’s what still frustrates Hope Arnold. She says throughout the 10 months her husband J.D. Falk was being treated for stomach cancer in 2011, no one would talk straight with them.

“All the nurses, all the doctors,” says Arnold. “everybody we ever interacted with, no one said, ‘You’re dying.’”

Until finally, one doctor did. And that’s when Falk, who was just 35, started to plan. He summoned his extended family. And Hope made arrangements for him to come home on hospice.

‘I Couldn’t Ask Anybody’

The day her husband was discharged from the hospital, Arnold was dropping off some paperwork when she bumped into one of his doctors.

“He hugged me and asked me how I was holding up,” she says. “And then he handed me a bottle of liquid morphine. He said, ‘You might need it.’ ”

Arnold says she handed the bottle back. She told the doctor the hospice was going to bring a machine that would administer Falk’s pain medication automatically.

“And he looked at me,” she says, “and he held my gaze for a second. And he put it back in my hand and he said, ‘You might need it.’”

She slipped the vial into her purse.

“When I got home, it hit me like a ton of bricks,” Arnold remembers. “And I said to J.D., ‘I think he may have given this to me so I can give you an overdose.’ And he said, ‘Maybe.’ And then we didn’t talk about it anymore.”

Over the next couple days, Falk deteriorated quickly. Arnold says the hospice nurse offered another euphemism: “He said, ‘He’s showing signs of imminence.’ ”

Arnold worried that Falk was in a lot of pain. But she couldn’t tell. She was afraid that if she asked, it would betray the thoughts she was having about that extra vial of morphine.

“I couldn’t ask the nurse that,” Arnold says. “I couldn’t ask anybody anything.”

If Arnold could have asked Stanford medical ethicist David Magnus, he could have explained what assisted suicide is – and what it isn’t. It is legal for people to take or give large doses of narcotics to relieve pain, even if a known side-effect is that it may hasten death.

“The difference really has to do with intent,” Magnus says. “And that’s a tricky thing because it has to do with what’s going on in the mind.”

In the end, Arnold didn’t do anything with the extra vial of morphine, and her husband died within days of coming home on hospice.

“J.D. never told me, ‘I do want you to give me too much morphine,’ ” she says. “Actually, I don’t know whether or not he wanted that. That’s not the point. The point was nobody could talk about it.”

‘Winks And Nods’

People don’t talk about it, but it happens. Just over 3 percent of U.S. doctors said they have written a prescription for life-ending medication, according to an anonymous survey published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1998. Almost 5 percent of doctors reported giving a patient a lethal injection.

Other studies suggest oncologists, and doctors on the West Coast, are more likely to be asked for life-ending medication, or euthanasia, in which the doctor administers the lethal dose.

“Those practices are undercover. They are covert,” says Barbara Coombs Lee, president of Compassion & Choices, an advocacy group. “To the degree that patients are part of the decision-making, it is by winks and nods.”

Coombs Lee’s organization helped tell the story of Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old woman who moved from California to Oregon to be able to end her life legally after she was diagnosed with a brain tumor. Now the organization is backing legislation in California to make it legal for doctors to prescribe lethal medication to terminally ill patients who request it.

Coombs Lee’s group guides dying patients on current law.

“We talk with people about how they might broach the subject with their physicians,” she says, “and quite frankly, how to play the wink-and-nod game in a way that doesn’t jeopardize their physician.”

It’s a game one San Francisco woman is all too familiar with. (KHN and KQED are withholding her name at her request to protect her privacy.) She lived in San Francisco during the 1980s and watched one friend after another die of AIDS.

“The guys would have fungus everywhere,” she recounts. “Horrible diarrheas, emaciation. It looked like concentration camp pictures.”

A lot of her friends begged for lethal drugs to end their suffering, and she and the other caregivers figured out which doctors were willing to help. The caregivers coached each other on how to speak to the doctors in code.

“We would tell each other, ‘This is the doctor,’” she says. “‘They’re going to tell you how much is too much to give, and then they’re going to give you too much.’”

Though she witnessed many deaths hastened in this way, she says she never administered the drugs herself. Her time would come 20 years later when her husband was dying of throat cancer.

Some of his symptoms were brutal.

“It was like a horror movie,” she says, recalling the tumors all over his neck. They would fill with blood, she says, and sometimes burst.

“There’d be blood on the walls, on the mirror, everywhere,” she recounts, “And he’d be panicking.”

They were warned his death might be ugly. He might choke. He might have a seizure. More than anything, she says, he was afraid of dying in a hospital, hooked up to machines, powerless.

“He made me swear not to let anybody hospitalize him. He made me swear not to let his family swoop in and take him away.”

At one point, he threatened to shoot himself to avoid that. A nurse dropped hints that there was a different way.

“I remember being told, here’s how much pain meds you can give,” she says, “but beyond this, he’ll probably stop breathing.”

Her husband made it clear to her that this was the way he wanted to go. Several times, she says, he reviewed the instructions with her.

Months later, he slipped into a coma. When the nurse said he looked like he was a day, maybe hours, away from dying, it seemed like another hint.

“And I remember standing there with syringes in my hand. Just standing there, with my hands shaking,” she says. She remembers thinking, “Okay, what goes with what?’ And I was all alone. And that was about the most alone I’ve ever felt. That I couldn’t tell anybody else.”

She injected the drugs. Then she crawled into bed with him and held him and talked to him for the next six hours.

“And he literally died in my arms. I was holding him when he stopped breathing. And it was really peaceful. He just sort of drifted away.”

For years, she had nightmares about holding the syringes, but today she is confident that she did the right thing. Her husband’s death was calm and peaceful and exactly what he’d asked for. But she resents that she was the one who had to do it, that she had no help and no real guidance from a medical professional.

“I don’t regret it, but I wouldn’t wish it on anybody else. It’s not fair. It’s not right,” she says. “It’s not like choosing to die doesn’t happen. We just make it be sneaky and we put it on the wrong people.”

This story is part of a reporting partnership that includes KQED, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Repositioning Patient Leads to Debilitating Injury, Exit from Bedside

Magnet® Conference Early Bird Deadline June 5

NINR Welcomes Four New Members to the National Advisory Council for Nursing Research

Facing Death But Fighting The Aid-In-Dying Movement

Stephanie Packer was 29 when she found out she has a terminal lung disease.

It’s the same age as Brittany Maynard, who last year was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Maynard, of northern California, opted to end her life via physician-assisted suicide in Oregon last fall. Maynard’s quest for control over the end of her life continues to galvanize the “aid-in-dying” movement nationwide, with legislation pending in California and a dozen other states.

But unlike Maynard, Packer says physician-assisted suicide will never be an option for her.

“Wanting the pain to stop, wanting the humiliating side effects to go away – that’s absolutely natural,” Packer says. “I absolutely have been there, and I still get there some days. But I don’t get to that point of wanting to end it all, because I have been given the tools to understand that today is a horrible day, but tomorrow doesn’t have to be.”

A recent spring afternoon in Packer’s kitchen is a good day, as she prepares lunch with her four children.

“Do you want to help?” she asks the eager crowd of siblings gathered tightly around her at the stovetop.

“Yeah!” yells 5-year-old Savannah.

“I do!” says Jacob, 8.

Managing four kids as each vies for the chance to help make chicken salad sandwiches can be trying. But for Packer, these are the moments she cherishes.

Diagnosis and pain

In 2012, after suffering a series of debilitating lung infections, she went to a doctor who diagnosed her with scleroderma. The autoimmune disease causes hardening of the skin and, in about a third of cases, other organs. The doctor told Packer that it had settled in her lungs.

“And I said, ‘OK, what does this mean for me?’” she recalls. “And he said, ‘Well, with this condition…you have about three years left to live.’”

Initially, Packer recalls, the news was just too overwhelming to talk about with anyone –including her husband.

“So we just…carried on,” she says. “And it took us about a month before my husband and I started discussing (the diagnosis). I think we both needed to process it separately and figure out what that really meant.”

Packer, 32, is on oxygen full time and takes a slew of medications.

She says she has been diagnosed with a series of conditions linked to or associated with scleroderma, including the auto-immune disease, lupus, and gastroparesis, a disorder that interferes with proper digestion.

Packer’s various maladies have her in constant, sometimes excruciating pain, she says, noting that she also can’t digest food properly and is always “extremely fatigued.”

Some days are good. Others are consumed by low energy and pain that only sleep can relieve.

“For my kids, I need to be able to control the pain because that’s what concerns them the most,” she adds.

Faith and fear

Packer and her husband Brian, 36, are devout Catholics. They agree with their church that doctors should never hasten death.

“We’re a faith-based family,” he says. “God put us here on earth and only God can take us away. And he has a master plan for us, and if suffering is part of that plan, which it seems to be, then so be it.”

They also believe if the California bill on physician-assisted suicide, SB 128, passes, it would create the potential for abuse. Pressure to end one’s life, they fear, could become a dangerous norm, especially in a world defined by high-cost medical care.

“Death can be beautiful”

Instead of fatal medication, Stephanie says she hopes other terminally ill people consider existing palliative medicine and hospice care.

“Death can be beautiful and peaceful,” she says. “It’s a natural process that should be allowed to happen on its own.”

Stephanie’s illness has also forced the Packers to make significant changes. Brian has traded his full-time job at a lumber company for that of weekend handyman work at the family church. The schedule shift allows him to act as primary caregiver to Stephanie and the children. But the reduction in income forced the family of six to downsize to a two-bedroom apartment it shares with a dog and two pet geckos.

Even so, Brian says, life is good.

“I have four beautiful children. I get to spend so much more time with them than most head of households,” he says. “I get to spend more time with my wife than most husbands do.”

And it’s that kind of support from family, friends and those in her community that Stephanie says keeps her living in gratitude, even as she struggles with the realization that she will not be there to see her children grow up.

“I know eventually that my lungs are going to give out, which will make my heart give out, and I know that’s going to happen sooner than I would like — sooner than my family would like,” she says. “But I’m not making that my focus. My focus is today.”

Stephanie says she is hoping for a double-lung transplant, which could give her a few more years. In the meantime, next month marks three years since her doctor gave her three years to live.

So every day, she says, is a blessing.

This story is part of a reporting partnership that includes Southern California Public Radio, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Back-breaking work? Nurses face extraordinary health risks

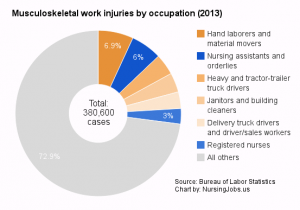

Nursing assistants, orderlies and registered nurses make up a significant chunk of the total number of back injuries suffered at work every year

NPR conducted an in-depth investigation into the working conditions of nurses, focusing specifically on how nurses suffer a shockingly disproportional number of back injuries. The authors concluded that “nursing employees suffer more debilitating back and other injuries than almost any other occupation — and they get those injuries mainly from doing the everyday tasks of lifting and moving patients”.

The NPR reporting was published as a series of articles, full of worrying data and heartbreaking stories, and the first four pieces alone added up to some 10,000+ words. Luckily the NursingJobs.us blog published a handy summary:

The post does some follow-up work too, describing some of the impact the NPR stories had, and taking a closer look at one of the hospitals where the reporters found management to have treated injured nurses particularly callously.

The writer also observes that the NPR stories haven’t been the only recent reporting about the health risks nurses face. Nurses working rotating night shifts have an increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease and lung cancer, recent research has found; nurses suffer depression at twice the rate of the national population; and health care and social assistance workers in general are four times as likely to suffer an injury or illness because of violence at the workplace as other workers.

![Safe patient handling: Be aware, be safe [quote, chart]](http://nursechronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/nursing_jobs_injuries_quote1-300x300.png)